AbstractBackgroundTraumatic brain injury (TBI) with intracranial hemorrhage management results in clinical practice variability, complexity, and/or limitations in acute care surgical and radiological workflow, which can prompt neurosurgical consultation, even when unnecessary. To facilitate an interdisciplinary practice for minimal-risk TBI, our objective was to create and sustain a neurotrauma protocol change that we hypothesized would not result in outcome differences.

MethodsA retrospective pre-post cohort study was conducted over an 8-month period to evaluate the protocol change toward trauma team management of TBI with isolated pneumocephalus and/or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) given a normal neurologic exam (i.e., minimal-risk TBI) without neurosurgery consultation. Demographics of age and Glasgow coma scale (GCS) were collected and expressed in means. Target outcomes consisted of protocol compliance, management compliance (e.g., nursing neurologic checks, thromboembolism prophylaxis, seizure prophylaxis, speech-cognitive testing, follow-up), neurological worsening, increasing therapeutic intensity levels, and TBI-related 30-day readmission.

ResultsOf the 49 patients included, 21 were in the pre-group (age, 54.19 years; GCS, 15) and 28 were in the post-group (age, 52.25 years; GCS, 15). There was 5% and 36% non-compliance with pre- and post-protocol practices in terms of neurosurgery consultation rates. In both pre- and post-periods, management compliance was similar, and none of the TBI patients experienced a worsening neurologic exam, increased therapeutic intensity level, or re-admission.

ConclusionMinimal TBI-risk protocol compliance was weaker after the practice change although management compliance and outcomes remained unchanged. This work supports that minimal-risk TBI patients with SAH and normal neurologic exams can be safely managed by trauma teams without neurosurgery consultation.

INTRODUCTIONManagement of severe brain injuries can require invasive neurosurgical intervention, such as intracranial monitoring, surgical removal of skull fragments for relief of cerebral edema, or surgical evacuation of intracranial hemorrhage. Minimal-risk traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), on the contrary, can be managed almost exclusively without surgical or invasive interventions [1] and such consults may be medically unnecessary [1,2]. Minimal-risk TBI can be defined as an injury of blunt mechanism with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) 15, no baseline use of anticoagulants/antiplatelets, no witnessed seizures, and admission head computed tomography (CT) radiographic pattern including either isolated pneumocephalus without displaced skull fracture and/or subarachnoid hemorrhage without displaced skull fracture. Further, it has been noted that neurosurgical consultation for management of these minimal-risk TBIs can overburden neurosurgery providers [1,2].

In one practice environment, brain injury guidelines were created and categorized TBI into three tiers based on a variety of injury-related radiographic and clinical factors. These three tiers of TBI were then associated with treatment plans [3]. This work supported that minimal-risk TBIs can be safely and effectively managed without the consultation of a neurosurgery service [3], and has the potential to reduce cost [4]. Variability in complexity and/or limitations in acute care surgical and radiological workflow can lead to neurosurgical consultation, even when clinically unnecessary based on existing evidence.

To facilitate a first step toward modifying interdisciplinary neurotrauma practice, our objective was to create and sustain a quality improvement protocol change for minimal-risk TBI management. We hypothesized the protocol change in practice towards exclusive trauma team leadership of minimal-risk TBI (i.e., no neurosurgery consultation) would not result in outcome differences with respect to protocol compliance, management compliance (e.g., nursing neurologic checks, thromboembolism prophylaxis, seizure prophylaxis, speech-cognitive testing, follow-up), neurological worsening, increasing therapeutic intensity levels, and TBI-related 30-day readmission.

METHODSA retrospective pre-post cohort study was conducted over an 8-month period to evaluate the protocol change toward trauma team leadership (without neurosurgery consultation) of adult blunt mechanism TBI patients fitting the criteria of minimal-risk TBI. The quality improvement protocol applied to individuals meeting the aforementioned inclusion criteria for minimal-risk TBI. For these patients, neurosurgery consultation was not indicated. These patients received neurological checks every 4 hours, a speech therapy consult was placed for in-depth cognitive evaluation, deep-venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis was held according to established institutional practice [5], and levetiracetam was ordered for post-TBI seizure prophylaxis per existing institutional protocol [6]. The admission head CT radiographic pattern was either isolated pneumocephalus without displaced skull fracture and/or subarachnoid hemorrhage without displaced skull fracture. Data sources included the electronic medical record, the trauma registry, daily trauma census, and radiology images.

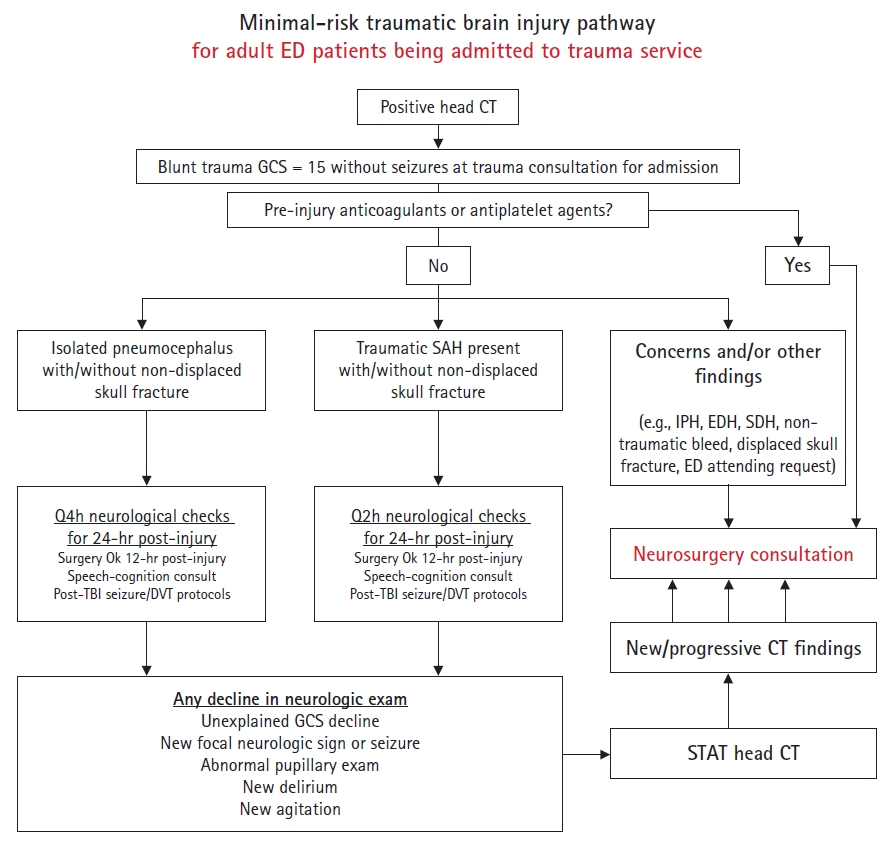

All other neurotrauma injury patterns on admission head CT were excluded (e.g., subdural hemorrhage, epidural hemorrhage, intraparenchymal hemorrhage or contusion, intraventricular hemorrhage, depressed skull fracture). Our quality improvement change also excluded patients with observed injury-related seizures or those on anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet agents (see Fig. 1 for eligibility criteria). This conservative focus on minimal-risk TBI patients served as an acceptable institutional strategy across the disciplines of emergency medicine, radiology, trauma surgery, nursing, and neurosurgery.

Our aforementioned eligibility criteria and protocol change (i.e., no neurosurgery consultation for those eligible) were incorporated into a management guideline (Fig. 1). The document was then disseminated electronically to all emergency department faculty and residents; trauma faculty, fellows, and residents; trauma advanced practice providers; multidisciplinary trauma performance improvement team members (including radiology); and neurosurgery faculty and residents.

Demographics of age, sex, and GCS were collected and expressed in medians. The mechanism of injury and initial head CT findings (brain injury type) were noted for each patient as well as the status of neurosurgical consultation (i.e., presence or absence). Our outcomes consisted of protocol compliance, management compliance (e.g., nursing neurologic checks, thromboembolism prophylaxis, seizure prophylaxis, speech-cognitive testing, follow-up), neurological worsening (as defined by decline in GCS of 1 or more points that is unexplained by alternative cause), increasing therapeutic intensity levels, and TBI-related 30-day readmission.

TBI management compliance was defined using five elements that were captured and identically relevant in the pre- and post-implementation periods. Orders were assessed for pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis being held for 72 hours following the time of admission for TBI [5]. Similarly, orders were reviewed for institutional seizure prophylaxis protocol compliance [6]. Formal cognitive evaluation by speech therapy and frequency of neurologic exams were also captured. Neurological exam orders placed outside of 2 hours from admission orders were considered compliance failure. Lastly, trauma clinic follow-up orders were assessed for compliance. Table 1 highlights the timing thresholds for each management compliance metric. Results are presented using descriptive statistics (n, %) for pre- and post-periods. Comparisons between groups were conducted using independent samples t-tests, chi-square, or FisherŌĆÖs exact tests. IBM SPSS ver. 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to conduct statistical analyses with alpha set to 0.05.

RESULTSOf the 49 patients included in this retrospective study, 21 were in the pre-intervention group and 28 were in the post-intervention group. Demographic information including age, biologic sex, admission GCS, mechanism of injury, and TBI type for each group is shown in Table 2. Subarachnoid hemorrhage without presence of skull fracture on admission head CT was the most common minimal-risk TBI type in both groups; pre-protocol (n=16, 76.2%) and post-protocol (n=25, 89.3%).

Of the patients in the pre-protocol group, 20 (95.2%) had neurosurgery consults placed for TBI management. One patient (5%) in the pre-protocol group had a neurosurgery consult placed for spinal injuries. For this patient, separate recommendations for TBI management were not included in the neurosurgery notes (i.e., protocol non-compliance). Ten patients (35.7%) in the post-protocol group inappropriately received a neurosurgery consult for TBI management (i.e., protocol non-compliance). In both pre- and post-implementation periods, management compliance was similar (Table 3), and none of the TBI patients experienced a worsening neurologic exam, increased therapeutic intensity level, or re-admission for complaint related to TBI within thirty days of discharge.

DISCUSSIONAlthough our minimal-risk TBI protocol compliance was weaker after the practice change (i.e., at times, older practices continued), our management compliance and outcomes remained unchanged, thus supporting existing literature that minimal-risk TBI patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and normal neurologic exams can be safely managed by trauma team leadership without neurosurgery consultation. When evaluating patient outcomes, none of the patients in either group meeting mild TBI criteria experienced a worsening neurologic exam that required repeat imaging, invasive measures, or escalation of care during hospitalization. There was no change in 30-day readmissions related to TBI. These results also support that a minimal-risk TBI patient can be safely and effectively managed without a neurosurgery consultation based on existing practice management guidelines [1,3].

One limitation of this minimum-risk TBI study is the sample size. Ideally, one future direction for this protocol change is to grow the target population to encompass more patients meeting the generalized mild TBI definition, as outlined in existing studies [1,7-9]. Another noted limitation is its retrospective nature. This could be potentially limiting due to reliance on the unstructured text documentation, and potential inability to note pertinent or confounding variables due to lack of documentation. In addition, the minimal-risk TBI population was a smaller, more conservative target population that may have limited our observations of adverse events. However, given priorities of patient safety, optimal implementation, and quality improvement, this approach of assessing minimal TBI patients was a strategically safe and appropriate first step. We noted an additional limitation where 35.7% of patients in the post-protocol group had inappropriate Neurosurgery consultations, and we believe this can be explained by the general challenge with implementing quality improvement change guidelines as providers tend to revert to historical practice. Another limitation is the reliance on different radiologistsŌĆÖ interpretations of head CT findings. Additionally, results may not necessarily be generalizable as this study was executed at a single academic medical institution, but we crafted our minimal-risk TBI protocol to be broadly applicable without a neuroradiologist, for example, clinical safety was prioritized over rigorous subarachnoid hemorrhage classification to facilitate execution in other institutions where this expertise is not available.

Strengths of this study include the analysis of objective measures such as order entry which can easily be evaluated in chart review. Standardized chart review processes also strengthened the data collection process of this study. However, there is general opportunity for improvement in each of the TBI-related management orders based on existing protocols and practices at our institution. A potential method for improvement could include an electronic order set within the medical record that would trigger providers to enter the target TBI-management orders. By developing a minimal-risk TBI order set, the template could then be copied into the consult notes of TBI patients, and therefore would prompt providers to order elements of the minimal TBI management pathway more consistently.

This study supports existing evidence that patients who present neurologically intact with low-risk, blunt mechanism TBIs with intracranial hemorrhage can be safely managed by a mature trauma team without the need for neurosurgical consultation. Although this was a retrospective cohort study on a subgroup of a mild TBI population, the results are encouraging for this protocol to be further expanded in a more generalizable mild TBI population. In summary, the implementation of a new protocol to manage minimal TBI patients without neurosurgical consultation yielded no significant negative patient outcomes and supports the claim that minimal-risk TBI patients managed with the application of this protocol are done so in a way comparable to a prior era with neurosurgical consultation.

ARTICLE INFORMATIONEthics statement

This quality improvement project was submitted to Institutional Review Board of Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Health Sciences Committee I (No. IRB00000475) and approved on May 2, 2019. Owing to the retrospective design, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Funding

This projectŌĆÖs study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation was supported by REDCap and Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research award CTSA grant UL1 RR024975/UL1 TR000445/UL1 TR002243 NCRR/NCATS/NIH. MBP was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM120484, HL111111, AG058639). All authors declare no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: all authors. Data curation: ESC, BAS, NRT, MSN, MDS. Formal analysis: ESC, BAS, MBP. Funding acquisition: ESC, BAS, MBP. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: all authors. Resources: all authors. Software: all authors. Supervision: BAS, MBP. Validation: all authors. Visualization: all authors. WritingŌĆōoriginal draft: ESC, BAS, MBP. WritingŌĆōreview & editing: all authors.

Fig.┬Ā1.Minimal-risk traumatic brain injury without neurosurgery. ED, emergency department; CT, computed tomography; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; IPH, intraparenchymal hemorrhage; EDH, epidural hemorrhage; SDH, subdural hemorrhage; Q4h, every 4 hours; Surgery OK 12 hr post-injury, surgery authorized on/after 12 hours post-injury; Q2h, every 2 hours; TBI, traumatic brain injury; DVT, deep-venous thrombosis.

Table┬Ā1.Minimal-risk TBI management domains A retrospective pre-post cohort study was conducted over an 8-month period to evaluate the protocol change toward trauma team management of TBI with isolated pneumocephalus and/or subarachnoid hemorrhage given a normal neurologic exam (i.e., minimal-risk TBI) without neurosurgery consultation. TBI, traumatic brain injury; DVT, deep-venous thrombosis. Table┬Ā2.Patient demographics of minimal-risk TBI

Values are presented as mean┬▒standard deviation or number (%). A retrospective pre-post cohort study was conducted over an 8-month period to evaluate the protocol change toward trauma team management of TBI with isolated pneumocephalus and/or SAH given a normal neurologic exam (i.e., minimal-risk TBI) without neurosurgery consultation. TBI, traumatic brain injury; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; MVC, motor vehicle collision; AC/AP, anti-coagulant/anti-platelet use; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage. Table┬Ā3.Minimal-risk compliance with TBI management

Values are presented as number (%). A retrospective pre-post cohort study was conducted over an 8-month period to evaluate the protocol change toward trauma team management of TBI with isolated pneumocephalus and/or SAH given a normal neurologic exam (i.e., minimal-risk TBI) without neurosurgery consultation. TBI, traumatic brain injury; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; Neurocheck complete, assesses the accuracy with which neurologic checks were ordered, such that neurological exam orders placed outside of 2 hours from admission orders were considered compliance completions; Neurocheck incomplete, assesses the accuracy with which neurologic checks were ordered, such that neurological exam orders placed outside of 2 hours from admission orders were considered compliance failures; DVT, deep-venous thrombosis. REFERENCES1. Ditty BJ, Omar NB, Foreman PM, Patel DM, Pritchard PR, Okor MO. The nonsurgical nature of patients with subarachnoid or intraparenchymal hemorrhage associated with mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 2015;123:649-53.

2. Overton TL, Shafi S, Cravens GF, Gandhi RR. Can trauma surgeons manage mild traumatic brain injuries? Am J Surg 2014;208:806-10.

3. Joseph B, Friese RS, Sadoun M, Aziz H, Kulvatunyou N, Pandit V, et al. The BIG (brain injury guidelines) project: defining the management of traumatic brain injury by acute care surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76:965-9.

4. Joseph B, Haider AA, Pandit V, Tang A, Kulvatunyou N, O╩╝Keeffe T, et al. Changing paradigms in the management of 2184 patients with traumatic brain injury. Ann Surg 2015;262:440-8.

5. Guillamondegui O, Hamblin S. Practice management guidelines for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.vumc.org/trauma-and-scc/sites/vumc.org.trauma-and-scc/files/public_files/Protocols/Trauma%20DVT%20Prophylaxis%20Guidelines%202016%20update%20for%20website2.pdf.

6. Patel M, Dewan M, Hamblin S, Banes C. Practice management guidelines for seizure prophylaxis: Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.vumc.org/trauma-and-scc/sites/vumc.org.trauma-and-scc/files/public_files/Protocols/Practice%20Management%20Guidelines%20for%20Seizure%20Prophylaxis-062116.pdf.

7. Lewis PR, Dunne CE, Wallace JD, Brill JB, Calvo RY, Badiee J, et al. Routine neurosurgical consultation is not necessary in mild blunt traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;82:776-80.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||